I met Pat Liddy at Davy Byrnes Pub. He’s wearing a suit and tie, with white hair brushed back, looking like the distinguished professor he is. And, since this is Dublin, he’s drinking a Guinness. He’s got his own tour guide company, and he has hordes of guides at his disposal—so it’s a treat to get a tour from the man himself.

I met Pat Liddy at Davy Byrnes Pub. He’s wearing a suit and tie, with white hair brushed back, looking like the distinguished professor he is. And, since this is Dublin, he’s drinking a Guinness. He’s got his own tour guide company, and he has hordes of guides at his disposal—so it’s a treat to get a tour from the man himself.

I feel a little bit intimidated. I told him I am a writer – but he has already written several books. As writers go, he’s way ahead of me. He’s got books you can actually buy, like in the bookstore and all. Despite my personal insecurities he is charming and soon puts me at ease.

He asks me questions and then talks to himself under his breath and then announces things he will show me. As we order fish and chips though, and as he asks more questions, he frequently changes his mind on what he has in store for me. None of it means anything to me. I’m not the type of traveler that shows up with his own ideas on what to see and do. I leave that for the locals. Some if it is no doubt due to personal failings on my part, namely laziness and ignorance. When he asks me if I want to see this church or that library, I shrug my shoulders and say, “Okay…”

And, in this, he sees an opportunity. Most visitors want to see the four or five “can’t miss!” sights in Dublin. Yet here is a guy – me – who is leaving it all up to him.

“Okay,” he finally says, “I’ve got it.”

We’re standing outside The Bank of Ireland. As banks go, this one is very nice. It’s huge and epic, with Doric columns and cannons outside the entrance. When we walk in, however, it’s a bank. There’s ATM machines and signs telling people to remove their motorcycle helmets and bank tellers and ads trying to get you to open accounts you don’t need. But the interior is ornate and striking. When you look up at the ceiling it gets even more so.

“This was the home of the Irish parliament from 1297 until 1800,” Pat says, “before it was dissolved by England.” Then, with a nod to one of the security guards, we walk through the bank and into the back room. Now we are in some sort of meeting chamber. Ancient relics line the walls, seemingly just lying around, waiting for a meeting that will never take place.

Pat likes to drop little pieces of bombshell trivia as if merely talking about the weather. “The official color of Ireland is not green,” he said.

“Wot?” asks the security guard who is acting as our escort.

“Nobody will believe you when you tell them, but the official color of Ireland is St. Patrick’s Blue.”

“Wot?” The security guard says again.

“And so the Irish Flag. It’s got Gaelic Green in it, of course. And orange for William of Orange. And the white in the middle represents peace. Didn’t work all that well though.”

“Wait,” I say, “St. Patrick’s Blue?”

“Yeah, we Irish like to muddy things up.” I’m thinking of all the green beer and green water and green beards and green beads and green all over the place every St. Patrick’s Day. I’m still thinking about it when Pat says, “Well, now that we’ve seen the bank we might as well go to the Post Office.”

The security guard is looking at the floor and shaking his head. His mind has just been blown. And he’s Irish.

We are now on O’Connell Street, the city’s main thoroughfare. The post office, like the bank, is very nice for what it is. Not as nice as the bank; but then, it’s a post office and much nicer than any post office in the United States. Pat is standing next to one of the building’s ornate Ionic columns.

“These are bullet holes,” he says, running his finger through a smooth divot. “And this was not always a post office. Let’s go inside.”

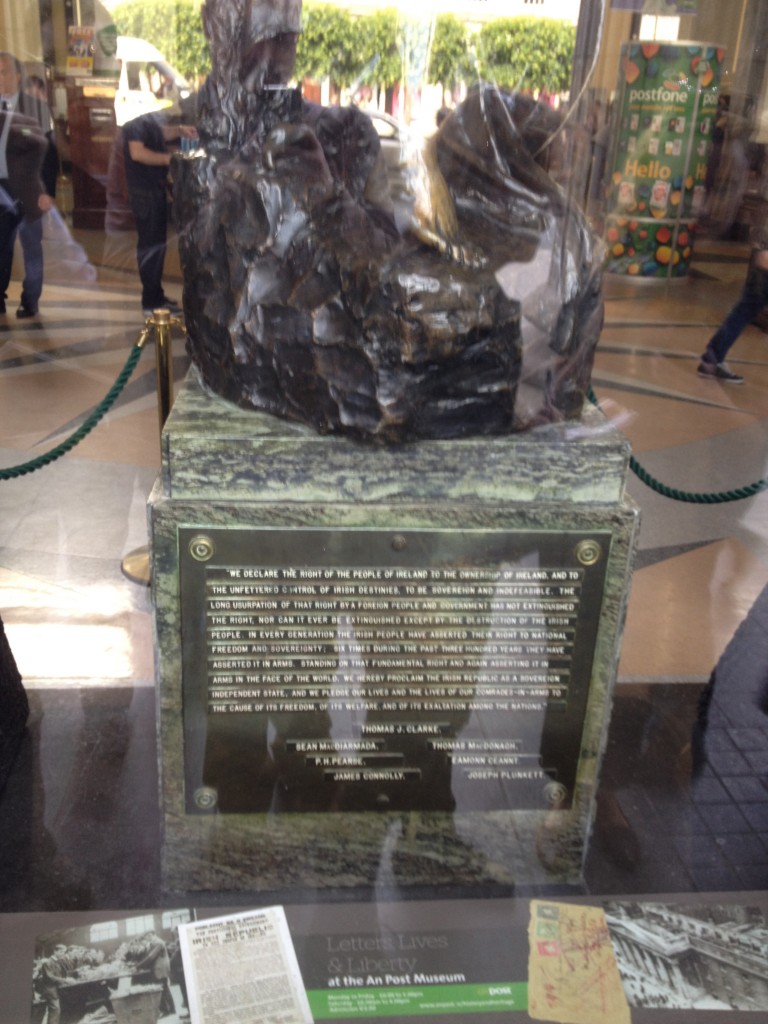

We go inside. “This was the headquarters for the leaders of the Easter uprising of 1916. The uprising was put down, and all of the leaders were executed, but what they started eventually led to the independence Ireland enjoys today.” In the window there is a plaque dedicated to the martyrs of Irish Independence. Next to it is a brief history of the building, which consists mostly of it being built then destroyed then rebuilt and destroyed again and then being rebuilt again. A lot of Ireland is like that.

“Okay. Moving on,” Pat says. He has a lot to show me and I’ve given him very little time in which to do so.

Pat Liddy is a fast walker. And it’s sort of deceiving. He doesn’t appear to be exerting himself in any way, yet you almost have to jog to keep up with him. He’s shorter than me and doesn’t have a long stride—he just moves. We walk past the Millennium Spire, which is a long shiny needle like structure that has been given a host of well-deserved derogatory nicknames. We walk past all manner of crap, such as Ripley’s Believe It Or Not and several souvenir shops and it all reminds me of Hollywood Boulevard before they turned it into a mall.

Finally we come to a church.

“A church,” I say.

“Precisely,” Pat says.

We walk in and it’s not a church at all, but a bar. This wasn’t a fake church that was a bar. This was an actual church, with no sign it’s anything else on the outside, that is now a bar. There’s still an organ on the inside. But instead of pews there are tables, and, in the middle, like an alter, are vast amounts of shiny gleaming boose. It was here, in 1761, that Alfred Guinness, the closest thing Ireland has to a deity, was married.

Pat is telling me the history of St. Mary’s Church, not that I’m paying much attention. It’s weird to be told of a church’s history when you are always having to move out of the way of waiters carrying trays of food.

“Nothing is as it seems in Ireland,” Pat says. “And you can fool all the people all the time.”

I couldn’t argue with that.

For more information on Pat Liddy’s walking tours, go here.